SafetiPin: What a women's safety app can teach us about artifacts and their politics

- Joyce Lee

- Nov 2, 2023

- 3 min read

Updated: Aug 22, 2024

Infrastructure built for men. An app built for women?

In 2012, the gang rape and murder of physiotherapy student Jyoti Singh triggered massive protests, as people railed against the authorities’ inability to protect women. 1,330 rape cases were reported in Delhi in 2013, a five-fold increase from 2012 (Mahapatra, 2013). Searching for answers, feminist activist Kalpana Viswanath co-founded SafetiPin, an app that collects user data to help women navigate the city safely.

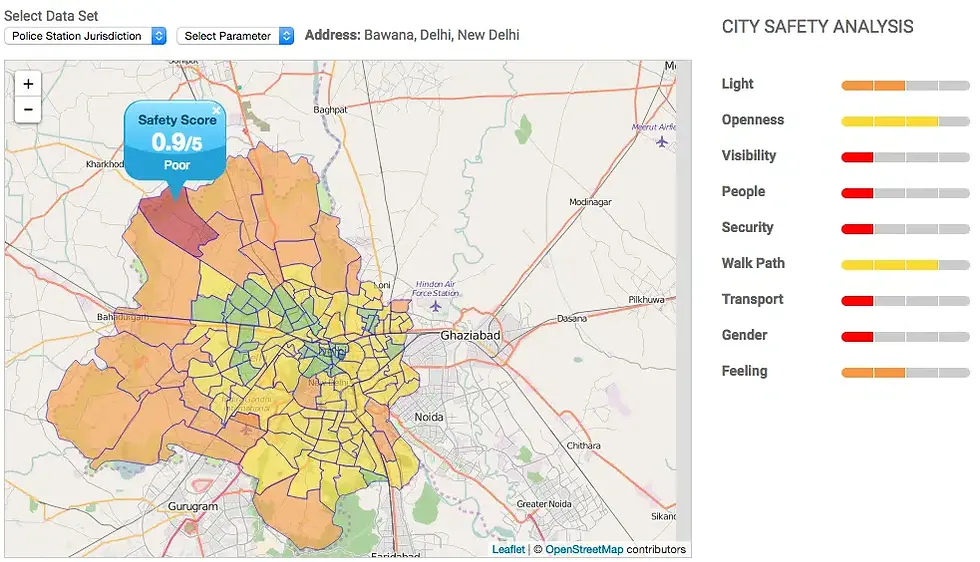

The app gives areas a safety score based on their lighting, visibility, openness, public transport, and other factors. Based on these scores, the app plans safest routes to the user’s destination. To audit user data, SafetiPin’s sister app, SafetiPinNite, collects night-time photographs of cities. Users of SafetiPinNite collect data by placing their smartphones on the windshield while driving.

SafetiPin was launched in Delhi in 2013 and has spread to 28 cities in ten countries. The app provides data to city planning authorities to help them build more equitable infrastructure.

The New Delhi Municipal Commission has used SafetiPin to improve lighting in dark areas. Delhi Police used the app to identify areas in need of more patrolling. In Bogota, 400km of bike paths have been audited with SafetiPin. Using the app data, the city’s women's security council (SDMujer) and transport authorities installed lighting, CCTV, and bike stands in areas with not enough (Serge, 2022). SDMujer and SafetiPin plan to conduct 12,000 face-to-face interviews to collect qualitative data on sexual harassment on the public bus system.

Graham and Marvin (2001) write that infrastructure networks are “inevitably imbued with biased struggles for social, economic, ecological and political power”. Similarly, Winner (1980) illustrated the political biases of infrastructure with the overpasses built by Robert Moses. These overpasses had low height clearance to exclude black and poor people from public parks.

SafetiPin arose as a tech solution to the politics of infrastructure. The lack of lighting and CCTVs in certain areas limits women’s mobility, necessitating the planning of routes. Apart from planning safe routes, the app works with city authorities to make streets safer. However, the implementation of SafetiPin might unintentionally reproduce biases.

As with any app, usage is limited by availability of mobile networks and smartphones. Low income neighbourhoods may not benefit as much from SafetiPin, as their residents lack smartphones and mobile data. Routes planned with user data from higher income areas might not be as relevant to low income women living on the periphery.

Furthermore, the app’s existence shows the long way our societies have to go. Baudelaire described the flaneur as an idler who wanders the city freely, taking in its aesthetic pleasures. The flaneur remains a gendered figure as women are still unable to roam the streets at ease. Apps like SafetiPin are a reaction to the dangers they face in public. In SafetiPin's 2022 report, the organisation highlights the pressure on women to move quickly from one sheltered space to another. They are discouraged from loitering in public spaces, especially on their own and after dark.

Technology can improve women’s safety, but the underlying problems still need to be fixed. The UN (2022) reports that women run one in seven environment ministries, and face barriers in city planning, construction, and leadership positions. With a lack of female voices in urban development, the design of cities will continue to suffer blind spots when it comes to women's safety.

References

Viswanath, K. (2016). SafetiPin: A Tool to Build Safer Cities for Women. Asia Foundation.

https://asiafoundation.org/2016/05/11/safetipin-tool-build-safer-cities-women/

UN. (2022). Making cities safer for women: UN report calls for radical rethink. https://news.un.org/en/story/2022/10/1129752

Graham, S. and Marvin, S. (2001). Introduction: Networked infrastructures, technological mobilities and the urban condition. In: Splintering Urbanism: Networked Infrastructures, Technological Mobilities and the Urban Condition. London: Routledge

Winner, L. (1980). Do Artifacts Have Politics? Daedalus, 109(1), 121–136. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20024652

Mahapatra, D. (2013, Oct 13). Crimes against women up. The Times of India. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/delhi/crimes-against-women-up-in-2013/articleshow/24953275.cms

SafetiPin (2022). She Rises: A Framework for Caring Cities. https://safetipin.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/She-RISES-A-Framework-For-Caring-Cities_Safetipin-1.pdf

Serge, S. (2022). Mapping Street Safety for Women and Girls in Bogota, Colombia. UN environment program. https://www.neighbourhoodguidelines.org/mapping-street-safety-bogota-colombia

Image credits:

Comments